Xavier Institute of Management

Bhubaneswar, INDIA | PGDM Class Notes | |

[Dec 24, 2008] Session 1: Introduction

Report by Soumik Tripathy (u107052)

The management curriculum is usually segregated into multiple functions. This enables us to focus on specific aspects of management, to delve deep into each area. However, to emerge as a business leader, one needs to have a holistic understanding of those functions and become aware of the linkages among them. To make one's learning in various functions (human resource, finance, information systems, marketing, operations, R&D, etc.) gel together, integrative concepts (e.g., system, structure, and strategy) are necessary. Like a capstone in architecture, these integrative concepts serve to hold together the fragmented ideas, giving an overall shape to our appreciation of management. Therefore, Business Policy (or Strategic Management) is known as a capstone course.

A business leader needs to appreciate the dynamic interaction among the various managerial functions. Consider the current downturn. Whether or not to increase production capacity during the downturn is a strategic decision the firm has to take. A prudent decision is only possible if the manager understands the issues in multiple areas, such as the issues of financing, market scenario--both current and future, supply of inputs, product quality, and so forth. A policy of lowering the capacity now might backfire later when demand increases and the firm faces stockout situations. It is not enough if the manager understands each function separately, without understanding their dynamic interaction. In reality, decisions taken in one function influence the outcomes in another function--sometimes irreversibly. For example, the procurement plans of a firm might reflect on the ease with which they can service the end customer, thus affecting customer satisfaction, which becomes a marketing issue.

Going by Mintzberg's model of organisational structure, the "strategic apex" requires a holistic perspective on the organisation and its overall functioning, without ignoring any part.

[Dec 26, 2008] Session 2: Business Environment

Report by Ankit Kanodia (u107006)

How business organisations are responding to the current downturn was the topic of discussion today. A cut in production (even production capacity) can be observed in some manufacturing sectors (e.g., metals, tyres). Although price reductions can also be observed in some sectors, firms manufacturing luxury goods are not cutting prices--instead, they are focusing on introducing smaller packs and improving customer service. This is perhaps to avoid any possible brand dilution. Despite the downturn and the liquidity crunch, certain industries are witnessing investment in big projects--presumably led by firms which have adequate cash reserves. In case of airlines, it is noticed that competitors are becoming collaborators to fight the reducing demand. Clearly, the impact of the downturn is not the same in all industries, nor is it the same for all the firms in the same industry. Some firms or industries may even stand to benefit from the downturn.

Some terms discussed in the class: (a) strategic decision, (b) derived demand, (c) fund-based and fee-based income, (d) inferior goods, (e) economy of scale, and (f) economy of scope.

Report by Naveen Urmese (u107079)

There was a discussion on the steps taken by companies in response to the current economic conditions.

1. Some companies have taken the initiative to be more transparent to their employees by opening new communication channels, such as CEO mails. This can be considered as a step taken to win the confidence of the employees.

2. There have been some acquisitions. This can be the result of the acquirer's optimism about the target company's prospects, despite a fall in the latter's market value. Alternatively, it could be a distress sell by the target company to meet its own financial challenges.

3. There are some new advertising campaigns, in different media, perhaps to suit the market sentiments. Example: "Let the bad times roll. Fly IndiGo in good times and in bad," says the new IndiGo Airlines advertisement.

4. Some companies are selling their assets to create liquidity. This issue is of strategic importance since it leads to reduction in capacity. The cost of creating this capacity could be much higher in future.

5. Some companies are trying to push innovation to fight inefficiencies and create new markets. Improving process efficiency to gain in bottom line can be a measure taken in case of products where price increase may not lead to profitability.

A key question raised in the discussion: Why do acquired companies underperform after acquisition?

[Dec 29, 2008] Session 3: Strategic Decisions

Report by Subhra Rath (u107054)

We discussed the eight major characteristics of strategic decisions and tried to map the Tata-Corus deal with those characteristics. Arguments about how this acquisition satisfies some of the characteristics, such as its impact on the long-term direction of the organisation, its potential for long-term competitive advantage, its role in matching the organisation's activities to the changing business environment globally, and its major resource implications, were discussed. Discussions centred around the distinction between strategic and operational decisions, recognising that the distinction is not always very sharp. Also strategic decisions at different levels of management was discussed, namely corporate-, business-, and functional levels. The active participation from two senior alumni who attended the session, Murali (PGDM 1988-1990) and Sadhana (PGDM 1987-1989), made the discussions interesting, as they shared their first-hand experiences with strategic decisions in their respective organisations.

Professor's Comment: This report can be improved by including more details.

Report by Naveen Urmese (u107079) and Niraj Kumar Mall (u107093)

We tried to map the eight characteristics of strategic decisions to the recent decision of two investment banks (Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs) to become commercial banks.

1. Affect long term direction: The long-term direction of the organisations has changed, since investment banking and commercial banking operations are quite different. Commercial banking comes under strict regulatory frameworks. It is also likely that, had they not taken this decision, they would have fallen like Lehman Brothers. A change from investment banking towards commercial banking would require new processes and exposure to new markets. It would also call for new vision and goals. Their business processes as well as the roles and responsibilities of their people will also change.

2. Achieve some advantage: Becoming a commercial bank creates an advantage-- they may be able to attract capital at a lower cost. But this may not be a sustainable advantage. Now these investment banks will be able to offer commercial banking to their clients.

3. Alter scope: The scope of both organisations has increased by adding commercial banking operations.

4. Match activities to changing environment: Trust on investment banks was declining after the events that had occurred over the last few months. This decision to go the commercial banking way will bring trust back to the system. There is a matching of activities to suit the environment of liquidity crunch.

5. Stretch resources or competencies: The existing resources of the organisation are stretched, for example, finance, technology, brand name, intellectual capital, etc.

6. Resource implications: It has major resource implications since they have to invest time and money for this transformation. They also need to attract people suitable for commercial banking.

7. Trigger operational decisions: Massive changes in operations, marketing, and human resources areas.

8. Expectations of stakeholders: Clearly affected by the values and expectations of both internal and external stakeholders.

Other things discussed: (a) organisations have tangible as well as intangible resources, (b) distinction between resource and capability, (c) three levels of strategy (corporate, business, functional). Strategic decisions are taken under circumstances where: (a) things are complex, (b) there is incomplete information, (c) the available information may be inaccurate, and (d) the outcomes are uncertain.

[Dec 31, 2008] Session 4: Strategic Leadership

Report by Niraj Kumar Mall (u107093), Nishith Sahu (u107094), and Srikanth Balasubramanian (u107111)

The class began with an exercise in which students were asked to place their footwears in a free space inside the class room. Students were then asked to have a look at the collection of footwear and write a description of it. A widely diverse set of descriptions were generated. Some described the unique attributes of each footwear (e.g., their different colours); some described the attributes collectively shared by the entire set (e.g., all of them being dirty). Some decribed the footwears per se, whereas some drew abstract interpretations from them (e.g., something about racism). Clearly, there was no one best description. People differed, along different dimensions, in their styles of description. Two dimensions could be identified: (a) level of uniqueness vs. level of resemblance and (b) focus on the material object vs. focus on meanings, implications, significations, etc. This led to the question of whether any particular style was more suitable for someone in the role of strategic leadership.

The distinction between "splitters" and "lumpers" was introduced, the terms indicating different ways of perceiving, describing, and thinking. Splitters are people who split things down into finer and finer elements for analysis and interpretation while lumpers are people who try to consolidate things together forming broad categories. Both are important and a strategic leader has to use the observations and ideas coming from both sets of people, even if these may, at time, be incongruent. A strategic leader has to obtain the best possible detail from a splitter and the best comprehensive summary from a lumper, and combine the same usefully to steer the organisation towards a desirable future.

The roles of strategic leadership were discussed next, highlighting the following key tasks: (a) taking strategic decisions, (b) creating a strategic position for the organisation, and (c) developing leadership capabilities among the members. To illustrate the challenges involved in the role of strategic leadership, the story of Compaq Computers was discussed, as it unfolded in the first two decades of Compaq's existence (1982-2002). Despite the phenomenal success of the company during this period, its CEOs were changed twice during this period--in 1991 and 1999.

A successful strategic leader is only successful within a set of organisational and environmental parameters. If, for any reason, the parameters get altered, it calls for the leader's capacity to adapt. Besides, a strategic leader needs to be in dialogue with the company's board, drawing upon the board's strategic thinking, while also contributing to the further development of that thinking. Moreover, a strategic leader must create organisation-wide commitment for a certain long-term direction, but when the environment changes, the leader must also be able to engineer a strategic renewal process, ushering the organisation into a new era. These make several conflicting demands on the leadership role, e.g., commitment to an idea while entertaining enough skepticism towards it.

The task of creating a strategic position calls for a clarity on an organisation's "generic strategy." Michael Porter's model showing four generic strategies was discussed.

[Jan 2, 2009] Session 5: Generic Strategy and Business Model

Report by Biswaksen Mishra (u107075) and Naveen Urmese (u107079)

Generic strategies are implemented through business models. For example, if the chosen generic strategy is "cost leadership," the business model should indicate a way for the oganisation to achieve the cost leadership status. Basically, business model is the underlying logic which drives the business towards the fulfilment of the chosen strategic goals. Different business models can achieve the same generic strategy.

Michael Porter suggested two sources of competitive advantage: cost and value. To implement either of these successfully, it requires an organisation to fine tune its objectives, resources, systems, and processes accordingly. When such an arrangement is refined to meet a particular generic strategy, then only the competitive advantage will be sustainable. Porter used the expression "stuck in the middle" to refer to those organisations which are neither geared to be cost leaders nor product leaders. But this idea has become debatable. Michael Porter suggested two sources of competitive advantage: cost and value. To implement either of these successfully, it requires an organisation to fine tune its objectives, resources, systems, and processes accordingly. When such an arrangement is refined to meet a particular generic strategy, then only the competitive advantage will be sustainable. Porter used the expression "stuck in the middle" to refer to those organisations which are neither geared to be cost leaders nor product leaders. But this idea has become debatable.

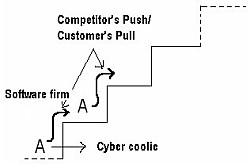

Strategy is about repeating the performance over the long term, i.e., achieving sustained superior performance over the long term. We discussed different ways in which one can sustain cost leadership. The idea of outsourcing was discussed. To sustain cost leadership through outsourcing, one has to constantly search for cheaper sources. R&D can also be a way to achieve cost leadership, for example through process improvements. The underlying logic of this can be represented by a cyclic process (see figure above).

Another approach would be to achieve cost leadership through investment in capacity, by utilising economy of scale (see figure below). Such cyclic processes should be at the core of business models. Another approach would be to achieve cost leadership through investment in capacity, by utilising economy of scale (see figure below). Such cyclic processes should be at the core of business models.

Any such logic would have its own limitations. In management, if anything seems promising, it must be promising under certain set of conditions. Accordingly, one needs to pay constant attention to business models and revise the model, or even replace it, whenever needed. For example, a capacity-driven business model will fail when the demand for the product is limited.

The case of a pharma company was discussed. Its main objective was to be a cost leader. It had its R&D set-up aiming at continuous process improvements. But the effort did not fructify even with top scientists and researchers. As it turned out, the whole set-up was geared towards more high-end research rather than the mundane work of process improvement. Thus, it is important to realise that there can be a mismatch between the abstract logic of a business model and the detailed processes through which it is sought to be realised.

[Jan 5, 2009] Session 6: Industry Structure

Report by Niraj Kumar Mall (u107093)

The discussion centred on the notion of structure. The example of traffic jam brought out the following points: There are events which can be observed at the surface level, on a daily basis. These are answers to questions like "What has happened?" or "What is happening?" There are patterns or trends which can be observed over a period of time. These are answers to questions like "What has been happening?" There is still a deeper level of understanding where the underlying causes are revealed. The causal factors and their interactions are observed at that level. This understanding can then be used to anticipate and even guide the possible future developments of a system. It helps explain why something is happening and in which direction the system is moving. Thus there is an "underlying generative mechanism" in each system which is called the structure. This structure provides stability to the system. The structure is harder to see, in comparison to events and patterns.

Thus an industry structure refers to an underlying generative mechanism that helps explain the events and patterns observed in the industry. With a good structural understanding of the industry, one can anticipate the future and steer the system to a more desired level. Michael Porter's five forces model is the most frequently used tool to describe industry structure. The five forces are: (a) threat of new entrants, (b) bargaining power of buyers, (c) bargaining power of suppliers, (d) threat of substitute products, and (e) rivalry among existing firms. Thus an industry structure refers to an underlying generative mechanism that helps explain the events and patterns observed in the industry. With a good structural understanding of the industry, one can anticipate the future and steer the system to a more desired level. Michael Porter's five forces model is the most frequently used tool to describe industry structure. The five forces are: (a) threat of new entrants, (b) bargaining power of buyers, (c) bargaining power of suppliers, (d) threat of substitute products, and (e) rivalry among existing firms.

These forces may be high or low in an industry depending upon a number of contextual issues. For example, if there are high exit barriers for the players in an industry, then the rivalry among existing firms is likely to be high. It was noted that entry and exit barriers can be different in different industries. More . . .

[Jan 7, 2009] Session 7: Resources and Capabilities

Report by Biswaksen Mishra (u107075)

Continuing the discussion on the idea of structure as the underlying generative mechanism, we concluded that one cannot fully understand a system by just knowing the data, charts, and trends associated with that system. To understand a system, one needs to understand the underlying mechanism that drives the system. That underlying generative mechanism--the structure--gives the system its identity, which is expected to be somewhat stable.

Any system has both time-variant and time-invariant aspects. We discussed the Indian software service industry, identifying some of its time-variant and time-invariant aspects: Any system has both time-variant and time-invariant aspects. We discussed the Indian software service industry, identifying some of its time-variant and time-invariant aspects:

* Time-variant (i.e., fast changing) aspects: technology, markets, nature of services, modes of delivery, mergers & acquisitions, business operations, etc.

* Time-invariant (i.e., relatively stable) aspects: product life cycle, outsourcing, rate of attrition, less capital intensive, long-term contracts, time zone, English speaking technical graduates, etc.

These invariant factors are the basic elements from which the industry structure can be modelled--the stable elements are far more directly involved with the structure. We then discussed a particular depiction of the structure of the Indian software service industry. Two key forces were identified, which have shaped the industry--competitors' push and customers' pull.

Finally we discussed about resources and capabilities--factors that make an organisation unique among its competitors. We started with the difference between resources and capabilities. Examples: the distribution network of a firm is a resource, skills of the employees is a resource; the ability to reach rural markets is a capability, the ability to upgrade the product frequently is a capability. Behind every capability there must be some resource(s). Most of the resources used by an organisation are not owned by it.

All capabilities of an organisation may not be equally relevant. Some may be more relevant than others vis-à-vis long-term objectives. These relevant capabilities are called strategic capabilities. A subset of strategic capabilities may be core capabilities--strategic capabilities which cannot be easily replicated or substituted by a competitor.

[Jan 22, 2009] Session 8: Strategic Options

Report by Soumik Tripathy (u107052) and Biswaksen Mishra (u107075)

"Everyone is World Champion at some game, although some of the games have not yet been recognized." -- Ross Ashby (1903-1972) (see other quotes by Ashby)

The generic strategies of Porter were revisited--cost leadership, differentiation (or product leadership), cost focus, and differentiation focus (or product focus)--and the associated debates surrounding the idea of being "stuck in the middle." The contribution of Bowman's Strategy Clock model were discussed. According to this model, it is always preferable for a firm to increase the perceived value of its offerings and decrease the perceived price or, at least, achieve one of these while maintaining the other. Not being able to do that could lead to long-term failure. Thus, the model indicates five potentially successful generic strategies.

There are other models of generic strategy too, for example, the Delta model. A generic strategy may not be sustainable in the long run. It needs constant managerial attention.

Strategic options may be seen at various levels:

Level 1: Generic strategy

Level 2: Business model (see Session 5 above)

Level 3: Product-market options (Ansoff's matrix)

Level 4: Method of development (internal development, merger/acquisition, strategic alliance, cooperative network)

A large proportion of acquisitions fail. Making an acquisition successful is a difficult challenge. According to Finkelstein, making cross-border acquisitions work is even more difficult. Read: Finkelstein, S. (n.d.). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions. (Summary of Finkelstein, S. [1999]. Safe ways to cross the merger minefield. In Financial Times Mastering Global Business: The Complete MBA Companion in Global Business [pp. 119-123]. London: Financial Times Pitman Publishing.) Retrieved January 20, 2009, from http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/syd.finkelstein/articles/Cross_Border.pdf

[Jan 23, 2009] Session 9: Capstone Simulation (Rehearsal)

[Jan 28, 2009] Session 10: Capstone Simulation (Practice Rounds)

[Jan 30, 2009] Session 11: Capstone Simulation (Practice Rounds)

[Feb 2, 2009] Session 12: Capstone Simulation (Preparing for Competition Rounds)

[Feb 4, 2009] Session 13: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 1)

[Feb 6, 2009] Session 14: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 2)

[Feb 9, 2009] Session 15: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 3)

[Feb 11, 2009] Session 16: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 4)

[Feb 13, 2009] Session 17: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 5)

[Feb 16, 2009] Session 18: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 6)

[Feb 18, 2009] Session 19: Capstone Simulation (Competition Round 7)

[Feb 20, 2009] Session 20: Discussion

Report by D. P. Dash

We reviewed our Capstone experience. Various items of learning were reported: (a) interconnections among the various decision areas, (b) negative effect of price war, (c) need to attend to various stakeholders, (d) lingering effect of bad decisions, (e) surprising results (or unintended consequences) arising from competitive dynamics, (f) recession mindset did not work, (g) need to rethink initial strategy, (h) role of organisational learning, etc.

Some of the final scores were compared. It was found that each company told a unique story. Analyst Scores or Balanced Score Card figures did not exhibit a one-to-one correspondence with financial performance. When losses were incurred, some companies came back to profit much faster than some other companies.

Finally, there was a demonstration of the Avalanche game, which was played with a bamboo ring of about 1 m in diameter. (The game was taken from a recent article by David C. Lane in the journal, Systems Research and Behavioral Science, published in 2008.) The task was to bring down the ring while not losing finger contact. It was found that, with four or more persons playing, the ring displayed strange behaviour -- moving horizontally, stalling at some level, or sometimes even going up! The exercise showed that unintended consequences can arise while performing a collective task, through a process of mutual adjustments to the variations introduced by the individual participants. Parallels were drawn between this and the Capstone experience. The invitation was to appreciate the multi-agent process of mutual adjustments involved in the strategy process.

|